No Higher Purpose - Introduction:

No Higher Purpose is a creative memoir based on a true story about a journey both worldly and spiritual that transforms Stuart into a warrior for inner Truth. Following the protagonist’s marriage breakdown, he seeks freedom from his troubles in Buddhist insight meditation.

After gaining a significant insight while on a wilderness retreat, seeking enlightenment becomes the focus of his life. It also kicks off his travels to Toronto, where he hooks up with single Mom, Delphine, to Norway, England, and some years later to India, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. These drama filled journeys form a backdrop for his spiritual seeking and the story’s building climax that leaves Stuart with no choice but to end his life to save others from himself. It is in this climate that the story shifts in an unexpected way.

Though this creative memoir is written by Delphine, her “voice” is interspersed with Stuart’s to give the reader deep insight into the dramatic life changing journey for both.

I am in the process of seeking an agent and / or publisher to take this book to the market.

The links below provide samples for your enjoyment, and to spark your interest. Once I have a publisher, I’ll add the Amazon link to this page. Until then, please be patient.

- No Higher Purpose – Story Opening

- No Higher Purpose – Meeting with a Jungle Ascetic in Mahabaleshwar India

- No Higher Purpose - Train Ride to Madras

No Higher Purpose – Story Opening

Prologue

As I stood in the snow waiting for our suitcases to be thrust onto the crudely covered outside bench that constituted baggage retrieval at the Whitehorse Airport, I knew my decision to leave Berkshire, my family, and our sheltered lives was about to kick my three-year-old son and me out of our safe zones. The 30-below chill pinched my nose, and a whole lot more since my pink wool coat, thin black leather gloves and matching heels might as well have been tissue paper for all the warmth they gave me. Faces watched through a frosty airport window. I turned my back, stumbled across the packed snow, and stood with my son beside the bulky-parka wearers while wondering if they knew how to drive a dogsled, in that cold.

But this story isn’t about my adjustment to Canada’s remote north, or how I started to unfurl my wings. This story is about someone I met there, the kind of someone who said, “Forget the wings,” grabbed my hand and leapt clean off the cliff.

I’ve been asked by some if I made the right life choices, which made me wonder if they were burdened with regrets of their own. I have no regrets, even if it wasn’t always an easy ride. Regretting the past is a pointless waste of time. Deal with it and move on.

I hooked up with the “cliff-jumper” not long after a Dharma Group psychotherapy course in Mexico. I’d been on this quest to change myself, to overcome shyness, my conditioning, a growing dissatisfaction with me. Mostly, I wanted to know why dreams and hopes disappointed, why life in real time felt so different from what I’d imagined.

Then, right on time, there he was. Grow, overcome, dissatisfaction. He had answers to all of them, the only question being was I up to the challenge.

In the early years, our relationship felt like emotional parkour—tough, alive, exhilarating, with the challenge to grow at the core of most everything we did. But challenges come with risks. I doubt any real challenge is free of threat. Failure itself hurts like hell. Don’t I know that, though he wasn’t the type to give up or fail, except when it came to relationships. They were not easy for him.

By the time Stuart reached Discovery Island off the southern tip of Canada’s Vancouver Island, he had become so close to the tipping point that . . . suffice to say not even I understand the danger he was in. He talked little in those days about what was going on inside his mind, as if I was beneath him, as if I couldn’t begin to grasp what had become of the man I met a decade back, the man who had loved me, and I him, with a glorious passion, and the man who was no more.

Stuart 1985

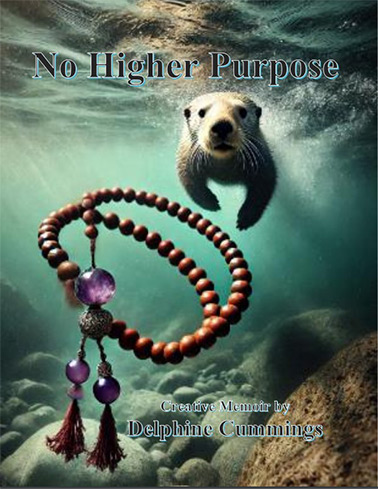

I undid the knot on the meditation scarf, lifted the mala over my head and stared at it. It felt as if I’d never looked closely before, but of course I had. I would barely move without it. The beads had been imprinted with the vibration of everyone, from the Dalai Lama to His Holiness the Karmapa, who wore a crown said to be woven from the hair of a thousand celestial beings.

The beads were smoothed by millions of journeys past my thumb and forefinger. Countless mantras, thousands of hours of inner and outer yogas, and not a single soul any better than when I began.

I couldn’t help my family, never mind save all sentient beings. I wasn’t even able to look after them, while an animal could do that.

A great sorrow welled up from deep within me and tears, like scalding water, slid down my cheeks. I lifted my fist, shaking it in sheer frustration, and suddenly I was screaming with all my might, yelling into the sky.

“If there’s anything in this universe that loves, you do it. I quit. I’m beaten.”

I smashed the mala to the ground and rolled onto my side with a sob. Nothing was left in me to fight. I was defeated.

No Higher Purpose – Meeting with a Jungle Ascetic in Mahabaleshwar India

I wandered into the rhododendron forest staring up at the enormous trees. Happy to be in nature, I loped along, noting animal tracks, and listening to whistling birds. It felt good to be moving, to be free of town, its stink and noise.

In an open area, I slowed to a walk. The ground was covered in thick grass, like a lawn in need of mowing. A string of boulders and smaller rocks lay strewn about as though once part of a wall or rockery in a garden long abandoned. Though the sun was high, light was subdued, barely filtering through the overhanging branches and thick foliage so that it painted shifting shadows on the forest floor. Through a larger opening in the canopy, pillars of light formed a cathedral light-effect.

The simple beauty and quiet of the place gave me pause, so I sat in the grass with a boulder as a backrest and began to meditate. Feeling tension in my shoulders drop, belly muscles slacken, breath starting to flow easily, I sharpened my concentration. The clench in my jaw softened. Adjusting my attention like the lens of a microscope, I was soon absorbed in the calming effect of deep concentration.

They say if you lean long enough against a ship weighing many tons, eventually it will move. So, it is with the weight of that which claims to be the self. You lean with the weight of concentration against swirling thoughts and ebb and flow of emotions. In time, they too move away. The serenity that arises produces bliss. The mind, unified in one-pointed concentration, enters the first level of absorption.

The hour ended. I opened my eyes. On the other side of the clearing stood a naked man, still as carved stone, one leg bent, sole of the foot resting on the inside thigh of the supporting leg in a classic yoga posture. In one hand, he held a staff topped with a trident, the sign of his mission, his life’s pledge to overcome greed, anger, and delusion to attain enlightenment. He was a jungle ascetic, a recluse, one of the true sannyasins of India. Bhagwan Rajneesh made a mockery of these men.

His flesh was sheathed in berry brown skin, with long hair and a whitish grey beard that exploded from head and face. I doubted I would have spotted him but for the starkness of three white lines painted on his forehead. The prince who became Buddha had lived and searched for truth no differently, their only requirement being met by walking into a hamlet and standing with their mouth open. Someone would hand feed an ascetic, thereby gaining karmic merit.

I put my hands together and bowed slightly. He responded by raising one hand to his chest in a one-handed salute and dipping his head. When I stood, his bent leg dropped. I walked across the grassy glade, and he mirrored my actions. A black and white butterfly danced through rays of light filtered by the trees. About three feet apart, we halted. Even close, his face remained obscure because no place existed where beard stopped, and hair began. I could not tell his age, but he was by far my elder. I put my palms together over my heart.

“Namaste, venerable sahib.”

He slowly placed a hand on his chest. “And I salute the light within you, mate.”

What? He’s English. I couldn’t come to grips with the fact that his gravelly voice sounded like our Cockney neighbors in Westbourne.

He told me he met his spiritual teacher in 1932, when a soldier in the British army. Because they wouldn’t release him in India even though his time had been served, he went AWOL.

I tried to imagine abandoning a Western lifestyle, even the Spartan life of a barrack room, for the hardship of the forest. Scars and scratches marked his bare body around which hung a small bag at his waist. A bone crucifix hung from a string at his neck.

He said nothing for a long moment. The leaves rustled in the branches above. Shadows and light flickered across his tanned face, center of the wild mane. I sat down on the grass, and he lowered his body, legs flowing into the lotus posture without aid from his hands. He closed his eyes.

An hour later, when my eyes opened, the forest sannyasin’s clear eyes met mine.

“Teachers are all right, lad, but trust God. He’ll find you.”

I felt two emotions simultaneously: anger over having to listen to someone else going on about God, and an odd sense of affection because he spoke to the essence of my dilemma. I told him I didn’t believe in God.

He smiled serenely and his words, while gruff, felt soft as falling snow. “What you think don’t mean nothing, lad. It’s what He thinks that counts.”

We sat for a few minutes.

“Your mate’s wondering where you’re at.”

I asked if there was anything I could do for him.

For a moment the mass of tangled hair and beard were eclipsed by an eye twinkle and smile. “Don’t ever give up.”

Like a perfectly shot arrow, his remark penetrated to the center of my lethargy and despair. In my heart of hearts, though I had gone too far to be able to live an ordinary life, part of me wanted to quit, head home, forget the whole thing, and be normal. In the struggle for enlightenment, wanting to quit was the same as quitting. India and Bhagwan had taken more out of me than I had realized. I stood up.

“Thank you, sir. I will never quit.”

He pulled a foot to his thigh, closed his eyes, and became still.

I strolled quietly from the glade. Just before leaving the clearing, I turned. I thought he had left until I spotted him stone still, sun lighting one side of his body, other half in shadow. A butterfly settled on his hair, then fluttered off. I turned and left.

No Higher Purpose – Train Ride to Madras

Ancient suitcases, boxes, bags, tied-up sheet bundles, and people filled the train aisle. I stepped over the belongings swinging my pack one way then another to avoid collisions. At my assigned row, I stared in irritation. Beside the barred window, in my seat, sat a middle-aged man dressed in a white gown.

The brass-numbered wooden bench seats of similar vintage to Bombay’s waiting room were graced with a skimpy pad covered in buff fabric, with no divisions from window to aisle. Each bench was supposed to provide seats for three people. The bench opposite had a woman, her two children, and an elderly lady beside her. A bag between the adults acted as placeholder for a fifth person. On my side, next to the man in my seat, two older men, wearing traditional Indian dress, leaned on canes. Stretching over the seniors, I raised my voice and spoke slowly.

“Excuse me, but I think you’re in my seat.”

He stared out the window.

“He can speak English perfectly well, and he hasn’t taken your seat by mistake,” the elderly lady said. “He’s just taken it.”

The train lurched, throwing me towards the seniors’ laps. Excusing myself, I pushed my pack into the crammed overhead rack, then barely caught myself as the train lurched again and moved steadily forward. A Sikh soldier came up behind me and greeted the young mother and children.

Frustrated, I stepped over a rolled-up mattress and walked to the door that opened to the outside connector between cars. Above the door, a multi-language sign and symbol stated that it was forbidden to build fires in the coaches. Huh. Imagine that. Pity it doesn’t say something about squatters. Outside, the wind tugged at my clothing, and the floor plates vibrated as the train thundered along. Then it squealed around a tight curve, engulfing me in sooty smoke. Driven back inside, I opened and re-closed the heavy door as a hush fell over the passengers. To hell with it, I decided, and strode over.

“Sir, your ticket, now.” I tapped the man on the knee.

His pudgy hand pushed mine off while he stared the other way.

“I doubt he has a ticket at all, and if he does, it certainly won’t be first class,” the old lady said. “Usually, they ride on the roof.”

“Appreciate your help, ma’am.”

Fed up with the shenanigans, I clutched the man’s knee with a weightlifter’s grip and squeezed hard. He yelped, shot from the seat, and stood glaring at me. I stepped back and jabbed my thumb over my shoulder.

“You, out, now.”

As I reached for him, he hunkered down. A muscled arm flashed by me, a dark hand grabbed the man by the throat and drove his head into the barred window frame, then, with a hard jerk, whiplashed it a second time.

A shiny blade fell to the floor. From my awkward position leaning over the old men, the soldier flicked his head indicating I should get out of his way. Using the man’s throat as a handle, he dragged the squatter into the aisle. Passengers watched.

The soldier barked an order as he half dragged, half walked the man towards the coach door. He turned to me and with another jerk of his chin made it clear I was to open the door. I pushed past the gasping man. The soldier forced the man between the two coaches and, before I could stop him, had unhooked the restraining chain, put his boot against the man’s backside and shoved him off the train.

The man hit the gravel, bounced, rolled, and was gone. The soldier, seeing my shocked expression, took me by the arm and steered me to my seat. I slid onto its warmth.

To my astonishment, the passengers clapped.

“Well done, sir,” one said.

“Serves the bounder right,” another said.

“Another fare cheater.” The elderly woman spoke the way I talked about serial killers. “They ride on the roof to save rupees. Serves them right.”

“Maybe he didn’t have any rupees,” I said.

“Then he shouldn’t be on the train.”

Karma: such a useful device to allow you to ignore others’ pain and make a man’s life worth less than a seat on a train. I remembered Colin’s remarks that what a nation believes determines what it must become.

One of the elderly gentlemen produced a giant Thermos, several glasses, and in a cultured Indian-English accent announced, “Teatime, my fellow seatmates. I was waiting until that scoundrel decided to get off the train.”

Passengers chuckled. A human being had been discarded like a rodent and they clapped as if watching a long putt at a croquet game. He offered me a glass of tea.

“Thanks,” I said, feeling as if he was the Mad Hatter. I sipped, waiting to grasp what the tea party guests understood.

Then my confusion morphed into worry. For five hours I fretted about aiding and abetting in a crime, with its rat-infested jail consequence. While civil with those nearby, I wrapped my arms about me and stared through the window bars. The sunset and the first of the evening stars shone near the horizon. The train hurtled through a vast empty plain. Surrounded by people, I felt utterly alone. The soldier fell asleep, his wife’s head resting on his chest, a little boy asleep in each of their laps, while I carried the burden of guilt for us both, like Atlas with the world across my shoulders. The train swayed and clickety-clacked along.

Something woke me. My buttocks and neck ached from two days sitting upright on hard seats. Then, in the distance, I heard a strange sound, like rushing water, or waves. I read fear on passengers’ faces.

The elderly woman informed me that it must be students rioting because of the new law that allowed untouchables to go to university.

Within moments, the train slowed. On both sides, screaming students jeered. Passengers started to thrust suitcases and bags up against windows. I gratefully watched someone unroll the mattress over the bars of two windows.

The shouting and screaming made it hard to think. My stomach and jaw clenched. The soldier in me wanted to act, but without weapons I had no idea what to do. Then the train stopped. Feet thundered over the roof. Peering over a case jammed across the window, I stared at the sea of faces surrounding our coach.

“Sātha nīcē Gandhi! Sātha nīcē Gandhi! Down with Gandhi!”

While the grandmotherly figure of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi could shoulder that blame, we were the ones being attacked. Up ahead, they dragged a screaming person from a coach. His piercing cry collapsed so quickly that my mind saw the knife at the throat and felt the slice of steel. Fear gripped me.

The soldier jumped up. With a jerk of his head, he indicated I should follow. “Help me lock the end door!”

I leapt down the aisle. He pointed to a rope around a bundle. I ripped it off and lashed the door closed. Satisfied that it would be difficult to open from the outside, we headed to the other end, now, the only way in.

Some passengers sobbed. Others sounded hysterical. Outside, the roar of the crowd increased as someone bellowed through a bullhorn. The soldier pulled me back. He told me to stay out of sight because if they saw a white man, they would tear me to pieces.

My throat tightened. My breath became shallow and rapid. I asked the soldier for a weapon. He had nothing but the thin-bladed knife from the seat thief. I told him the knife made me feel better about the thief being thrown off the train. He looked shocked.

“In Canada, we would be in big trouble,” I said.

He leapt past me and swiped at an arm reaching for the door handle. “This is India, white man. The weak perish. Understand?”

The students at our windows tried to pull off the bars. The coach swayed from the force of their efforts. Their hate-filled faces howled in rage.

India was a hard land. One minute I was shocked at someone being thrown off a speeding train, the next wishing for an automatic rifle. With a couple of strides to the door, I landed with my body weight on the elbow of a man reaching for the door handle. Its owner shrieked and withdrew.

Another hand groped for the handle. Again, I kicked. A scream, and the arm disappeared. In the midst of the horror, I flashed on a baby photo of me teething on Dad’s army pistol. I mentally thanked him for my tough upbringing.

The train lurched violently and abruptly stopped, throwing us off our feet. We scrambled up in time to see the coach door swing open to the raging mob. Men pulled themselves into the coach. We jumped forward and lashed out, punching and kicking. A student screamed as the soldier’s boot crushed his nose. The intruder tried to back up, but the crowd pressure pushed him forward. Other young men climbed in, thrust by the surging crowd. Women in our coach screeched each time we hit someone. Outside, another person screamed and abruptly stopped.

There was nowhere to go, nowhere to run.

Kicks flew, blood splattered, one face disappeared to be replaced by another.

Suddenly, I was being dragged. I lunged, grasping for a seat leg, but the pulling was too strong. I slid towards the door. The Sikh’s knife flashed. The attacker gave a high-pitched scream. I flailed madly, trying to free my leg. The knife flashed and brown hands bled. The attackers let go.

My fear turned to rage, and I screamed in fury as I kicked at those who would tear me to shreds. I kicked to kill or maim. My military training burst free of the restraints in which I normally contained it. I aimed at finger joints, eyes, throats, or noses, snapping my foot back the moment after contact, no longer fighting to defend, but to kill or be killed.

In the middle of my rage, I felt a hand on my shoulder. The soldier took my place. I bent over gasping for air, sweat pouring.

I stood again when I heard the Sikh in the center of the doorway, roaring at the crowd. I knew he invited anyone who wished to die to come forward. Some jeered insults. The knife stabbed, rioters screamed, and the crowd stalled.

Then, I saw it.

I had heard of it, but never thought I would witness it. Occasionally, we young soldiers managed to get a combat veteran to tell us of battles in Korea or Europe. Sometimes they spoke in awed tones of men who became transformed in the heat of battle. The Sikh willed that change to take place. His eyes smoldered; his body seemed to grow larger.

Warrior poets talk of blood “singing in their veins.” I witnessed it. I witnessed the manifestation of a warrior. The Sikh’s pride, his wrath, and his willingness to die fighting transformed him. No one in the mob dared meet his eyes or accept his challenge.

The crowd wilted, collapsing in on itself as fear replaced madness. Their rage at political and spiritual masters was inadequate. His proud stance mocked them, while his glare stoked their fear like fresh coal to the train engine’s furnace.

In the sea of people surrounding the train, a single spot around a single coach started to thin. Faintly, a shudder passed through the steel decking. The train slowly gained speed.

The Sikh made space for me beside him and together we watched the faces recede. My mind, still buzzed with adrenaline, threw up questions about why yet another disaster had come my way. Without both our military backgrounds, I would be dead. That much was certain. But what any of it had to do with my enlightenment quest remained a mystery.

The trip continued without event, though the shared danger had bonded us. The soldier told me a little of his life as a boy in the northern mountain country. I found it no surprise that he came from a long line of soldiers who had served in the British forces. As the memory of his courage resurfaced, I thought of the naked sannyasin in the rhododendron forest and the suffering I had seen. I needed to go to ground and stay with my back to the wall until I had won the enlightenment battle or died trying.

I could try Sri Lanka, though it felt like a long way to go. Perhaps I should go home. I decided to think about it in Madras.

I watched the sleeping soldier’s family, boys sprawled across their parents in the comfortable abandonment of children. They knew in their little hearts that they were the pride and joy of this lovely young mother, with her long dark hair, her yellow sari with threads of gold along its edge, and faint smell of jasmine about her. Sometimes she would push a son’s forelocks back with small soft strokes of her hand.

I thought of Delphine and the coming birth.

What contrast with the girls Rajneesh had doomed to be childless. A great sadness washed over me as I recalled their young faces and remembered their earnest commitment. If this mother decided to strive for the great awakening, it would be the love of her sons that empowered her, not being used at an orgy.

Hopefully, Colonel Virdee could do something about Bhagwan. It seemed odd that you could command an army but not take out one magician.

The train rumbled through the night. Even after I had wearied of my own weariness, I couldn’t sleep because I would jolt awake dreaming that I slid towards the coach door.

Late afternoon of the next day, I shouldered my backpack and trotted down the steps of the Madras station. After days of shuffling along aisles filled with baggage, walking felt relaxing. A cool breeze brought a faint smell of the ocean. Madras, a coastal city like Bombay, seemed cleaner than the city into which I had flown two and a half weeks back.

Movement above me threw a shadow on the sidewalk. I looked up. A man hung from a lamppost, rough hemp rope around his neck, probably a remnant of the riots. In the hot sun, the body swung slowly about.

“The untouchable thought our laws would protect him.”

I jerked around, ready to defend myself, but stared instead at the Sikh soldier. His family waited in a taxi. As I let out my breath, he clapped me on the shoulder and said he was sorry for my bad experiences and wished India had shown a better face.

“Many troubles right now. Unrest in our people as well.”

I remembered Major Singh and held my tongue.

“Namaste,” he said. “Truth is eternal but keep your knife sharp.”

I gave a small bow then waved to the taxi occupants. Despite my smile, the ugliness of humankind lay in my belly like parasites.

Another taxi pulled up to the curb. “You want to go someplace, sahib?”

“Yes, out of India. Take me to the airport.”