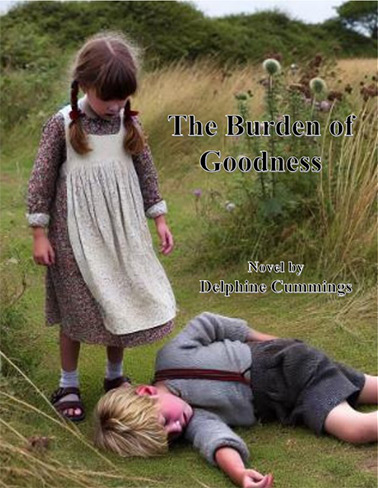

Burden of Goodness - Introduction:

Can a father, who lives life being good and honourable even when it thwarts his hopes of saving his business, succeed? Can his ten-year-old daughter experience a coming of age?

Burden of Goodness charts the progress of a family battling adversities. The father, Arthur Lindgren, must decide whether to remain true to firmly held principles at the risk of financial ruin. These challenges are compounded by the revelation that his financial backer is behaving inappropriately with his daughter. Her struggles centre around early sexual explorations and a severe telling off that leads her to be convinced she is bad. This badness with no redemption becomes clear when this middle-aged man starts kissing and touching her. “Bad things happen to bad people,” she concludes.

When you look past these not entirely ordinary lives, when you peer beyond the day to day and watch the daughter become a May Queen, enjoy a visit to a coronation, suffer snowstorms and pneumonia, when you venture into England’s East Coast floods and take a detailed look into pharmacy’s medicine making of old, and much more, each moment forms a thread in the story’s blanket that evokes imagery of another time, of different values, almost regretfully, long gone.

I am in the process of seeking an agent and / or publisher to take this book to the market.

The links below provide samples for your enjoyment, and to spark your interest.

- Burden of Goodness - The Tower - 1952

- Burden of Goodness – Queen Elizabeth II

- Burden of Goodness – Mildred - 1914

Burden of Goodness - The Tower - 1952

Heatherbelle was doing her utmost to clamp down her dread that she and her siblings would be dragged off to prison for being involved in Carl’s death.

The day before, her ten-year-old brother David had come home from school excited. “You won’t believe this,” he exclaimed. “Carl wants to jump off the Tower on the Moor this Saturday! You’ve got to come watch.”

“Why on earth would he do that?” she’d asked. “You’re not going to jump too, are you?” She leaned forward, all too aware of the schemes her big brother and Carl got into. Could he be teasing her? He did that often enough, knowing how she always reacted.

“Of course not,” David said.

She didn’t believe him. The way he looked away quickly. Pretended he was just eating his apple slices.

“What if Carl bashes his brains in?” she said, frustrated for not being sure of David’s intentions. “We’ll get into the worst trouble ever. I’m going to tell Mum.”

“Don’t you dare.”

Their mother wandered into the living room.

“Mum, guess what, On Sat—”

David kicked her viciously under the table.

“Owww, meanie.” Now she knew something was wrong.

“What’s going on, children?”

“Nothing,” David said.

Heatherbelle stuck her tongue out, kicked David back, but missed.

The sunny August Saturday arrived with Heatherbelle still unable to persuade David to call it off. Reluctantly she and Drew joined him on the bike ride to the tower. Since Drew turned five, their mother insisted that David and Heatherbelle take him on their adventures.

As they pedalled up Horncastle Road, David warned Drew about the planned jump.

“If you die, I’ll be orphanized,” Drew said.

“You have to lose your parents to be an orphan, dimbo,” Heatherbelle said, peddling hard to come alongside David. “Anyway,” she shouted over her shoulder, “He’s not jumping or dying or I’m going to tell Father.”

“We can’t tell,” David said. “I promised Carl.”

“Father’ll find out,” Heatherbelle said. “He always does.”

“I’m not jumping,” David said. “So, shut up.”

“Promise.” She looked sideways at him.

For a while he didn’t answer. She gripped the bike’s handlebars tightly. Dreading what could be coming. In her heart she knew that part of David wanted to jump. Wanted to be as daring as his friend. Maybe, because of his horrid asthma, he wanted to die. No, no, no. Not that. She tried to banish the thought from her head. Would she want to die if she was him?

“I promise.” He stared ahead, blond hair ruffling in the breeze.

Heatherbelle sighed. Thank goodness. David wouldn’t break a promise.

Just beyond the outskirts of their village, beside the tall tower that stood in a huge rough grass field near the golf links, the three Lindgren children met up with Carl. Before Heatherbelle had a chance to give Carl the miniature tower that she’d brought with her, David instructed her and Drew to stand well clear. He and Carl then entered the medieval tower. The four-story stair turret, remnant of a Cromwell Tower-on-the-Moor hunting lodge, shot upwards 65 or so feet from its sloped base like a brick tree-trunk. Heatherbelle knew that if Carl jumped off the tower, he’d almost certainly hurt himself. If he jumped from higher up, he would die.

She squeezed the miniature tower in her hot hand. Luke had given her the carving to persuade her to stop beside the privet hedge. That was when her wickedness began. She’d kept the tiny tower locked in her secret box as if it stood for the bad thing that she and Luke had done each day, before the telling off.

It turned out the carving belonged to Carl, not Luke. It should never have been in her possession.

Wanting to be rid of the reminder of her wickedness, she’d planned to return the carving to Carl before he climbed the tower but had missed her chance.

Carl was David’s very best friend. What if his stupid jump wrecked him, or worse? How terrible that would be for everyone. Oh dear. Why hadn’t David let her tell their parents? It was so confusing. She knew deep down that somehow this mess must be connected to her other troubles. The bad troubles that had started with the little carving of the same tower.

Was that how things happened? Uncomfortable memories like jumbles of coloured wool difficult to untangle. She twirled her plaits as she stared at the tower. Pretty little Heatherbelle disliked her hair, neither straight nor curly, neither dark nor blond. Rat brown, she’d decided. Rat brown hair that frizzed like a mop when she didn’t plait it.

The boys appeared at the second of the tower’s elongated gaps, turned and disappeared. She held her breath. What was wrong with a lower floor? At the third, they waved briefly. Heatherbelle’s fretting turned to panic. Was Carl going to jump from the top gap? He would die for sure. She couldn’t bear to think about David jumping. She absolutely couldn’t watch that.

She’d given up any idea of scaling the tower to see the view when she saw the steps had crumbled requiring clambering up tiny brick ledges and jutted masonry.

Carl waved from the top gap. David, behind Carl, waved too.

Her stomach knotted.

Carl climbed onto the gap’s wide edge.

David promised. He promised. He promised.

With no warning, Carl shouted something she didn’t hear, and jumped. His body plummeted, hit the ground hard, and crumpled, face down.

Heatherbelle screamed. “No, no.”

Horrified, she looked up to where the boys had been, then down to the body of Carl Jasinski near the tower’s base.

Seeing the boy fall, witnessing his plunge struck something animal in Heatherbelle’s core. She felt a desperation eating at her belly as she’d not felt since the playroom incident. Since that other horrible moment in her life when the truth about her and Luke came out. She should’ve known that Carl couldn’t simply get up from jumping and walk away. That he might get injured or die. When she didn’t control things, they went sideways.

Big bad accidents happened where people died.

Big bad truths came out.

From now on she would never let go that control.

She wanted to turn and run so badly that her head swam. Why had David let this happen? Why had he chosen to be right there up the tower as if begging to be a part of the disaster? Why had Carl jumped? What made a boy want to end his life?

Avoiding thistles and nettles, she pushed through the tall grasses that tickled her legs and stumbled over the rough ground. The fall and thump as Carl’s body hit the ground pulsed through her mind. She brushed whisps of hair off her forehead.

Staring at Carl’s rumpled grey pullover, she knew she should have told their father. Too late for that now. An ant scurried over Carl’s bare leg.

She didn’t dare move the boy, though she used her sandals to push aside nettles touching his arms, face, and legs. Some nettles bounced back up, so she found pieces of old brick to pin the stinging leaves. David appeared from the tower and started walking over. His face was as white as pillows.

“Is he dead?” Little brother, Drew, strolled over from the other direction as he flicked nettle tops with a stick. “He looks dead. Dead as a doorpost.”

“Doornail, silly,” Heatherbelle said. “How many dead people have you seen?” She pivoted her sandal on a nettle.

“There’s a dead blackbird near Coronation Hall. Ants were eating its eyeballs.”

“People. Not dead blackbirds.”

“He looks dead.”

“Doesn’t.” Heatherbelle was determined to keep him alive.

“If he’s dead, they’ll blame us.” David padded over. “So, he’d better not be.” He wheezed.

Heatherbelle shot him a glance.

Carl’s right shoulder bent upwards; his arm twisted backwards like a bird’s broken wing. David touched his fingers to Carl’s neck.

“What’s that for?” Heatherbelle said.

“To see if he’s alive.” He moved his fingers to another part of the neck then stood up. “Drew and I are going to the Polish Camp to find his mother. Or phone the doctor. H, you stay here.”

“Me?” Her screech shot out like a scalded hand from dishwater. “Do I have to?”

What if he woke up and needed help? What if he turned over and she saw his mashed-in face? What if he really was dead? But there was no one else to go and no one else to stay. Drew was too little to do either and David should be the one to get the doctor. Drew needed to go for support.

“I’ll stay,” Drew said, in his Sir Galahad voice, chest puffed out. “I’m not scared.”

“I never said I was scared. Anyway, you’re too little.”

“You’re too little,” David said. “Mummy wouldn’t like that.”

“I’m always too little.” Drew whacked a thistle.

“Please be quick.” Heatherbelle watched the boys walk away. It wasn’t far to the Polish Camp. They’d be back soon.

She crouched down beside Carl, pulled her frock over her knees and stroked Carl’s back like Mummy putting their baby cousin Jacob down to sleep. His jumper felt lumpy where burrs and barley-grass seeds clung to the wool. After a few strokes, she pulled at one, then another, and another. Here and there the jumper had unravelled, and its hem frayed like the gypsy ladies’ long skirts. A gathering of grey fluff, burrs and grass seeds grew on the dock leaves next to her knees.

She could slip the carving into Carl’s trouser pocket, but if he woke up, he would know someone had put it there. Someone who shouldn’t have had it. Returning it now wasn’t going to be that simple.

Heatherbelle stood up, wandered a few feet, returned, and again crouched. Was it his shoulder first and then his head that hit the ground? Had she forgotten already? It had sounded like nuts squashing under a tea towel. Yes. She’d heard that horrible sound. They would ask. Did a person become an it when they died?

Where was David, and where was Doctor Amberley?

Would David go to prison? She and Drew, too? Without a doubt, the Lindgren name would be dragged through the mud. No one would come to Father’s chemist shop—already in financial trouble, Father had said. Boys always took risks, Father said. She knew better. She should have been in charge, then none of this would’ve happened.

On the left of Horncastle Road, past the outskirts of Woodhall, stood the Tower on the Moor, the finger of worn bricks that Heatherbelle wished had stood near someone else’s village a hundred miles away. That way the Lindgren family couldn’t be mixed up with Carl Jasinski who now lay in a slumped lump at the foot of the tower.

Heatherbelle stood up. It felt as though she’d been left alone with Carl for hours. In a whispery voice, beside the boy face down on a thistle and nettle patch near the golf links, Heatherbelle sang a few lines of her favourite hymn because she’d run out of ideas to pass the time. She badly needed to pee.

She hummed the tune again. Chariots of Fire, her secret helper in times of trouble. Life, after all, was dotted with troubles like burn marks on the hearth rug. Aside from getting the cane in class for something she didn’t do or going to the sideboard and finding someone had eaten the Fru Grains, the really big trouble, at five, was when she found out that she was a bad person. Not long after she’d been pushed into the Jubilee Pool deep end and nearly drowned.

Bad things happened to bad people and she and Luke had been very bad, or so it seemed.

Burden of Goodness - Queen Elizabeth II

Heatherbelle had loaded so much onto the day’s shoulders that it should have come as no surprize when her hopes regarding Emeryk fell short. Unlike May Day, she was merely one girl in a classful, many bolder, perhaps prettier with their fancy new dresses outshining her old swirly green skirt by leaps and bounds.

With worries about the family’s financial troubles, the move to Riverside never far from her mind, she slid quietly inside herself determined, despite that, to enjoy the coronation show.

The central London streets overflowed with people. It had rained earlier. The air felt brisk. Decked out in their going-to-a-coronation finery, most were draped in gabardine and hats, umbrellas ready. They stood in thickening throngs behind barriers. It had been a long wait. Some spent a night on the street. Small price to pay for a favoured spot on the procession’s route. London Bobbies, helmets brushed, shoes polished, faced the crowds. The people who didn’t stand, sat in deckchairs, on folded raincoats or blankets on the swept, wet pavement. Here and there a lucky one had his or her back to a building, a lamppost or red post box. Children sat cross-legged or ran around and got into trouble. Many older folks, unused to extended periods scrunched close to the ground, slouched, their legs slung beneath them.

Despite this damp June day in 1953, some lay flat on their backs, a hat or newspaper over their faces. Heatherbelle and her classmates, up since an unearthly hour, had spent the day sitting or standing in waiting rooms, on trains—three steam trains, two underground trains—and now in their designated school-spot they stood on the pavement waiting for the horses and carriages.

Down the street, with gusto and knee slapping, a group wearing Union Jack hats sang “Knees up Mother Brown.” A teacher told his charges to “Stand still and stop running around.” Clouds littered the road, reflections in the puddle-pockets dotting the empty tarmac. In the distance, a single soprano voice struck up above the natter and chatter, above the knee-slappers and crying toddlers, like a star on a cloudy night.

“And did those feet in ancient times, walk upon England’s pastures green . . .”

Shivers ran up and down Heatherbelle’s spine. Her song. Moisture clouded her eyes. She was tired. The voice continued to sing above the crowd and as most heard, they stopped talking. A deep bass voice joined in, then another soprano that sounded like a boy. Soon many on the street were singing, even the dum-da-di-dum folks who didn’t know the words. As it ended, they started again. On its second round, Heatherbelle joined in with Luke, Emeryk, Pamela, and Janet. Even Pricilla.

The spirit of the ceremony, the British ceremony, the crowning taking place at Westminster Abbey right then, sang out in everyone’s heart. This was England. This was their land, their home. By far the biggest celebration since the end of the war. In that moment it became a surrogate release of their love for their country, for God’s thanks that war had ended, and they’d been spared. In their hearts, they had all fought and lost something or someone to protect the freedom of their homeland. More than one shed a tear. Many put their arms over another’s shoulders, around their gabardineed waists.

Somewhere in the middle of the third time hush started. From far to the left it surged to where Heatherbelle stood, like a wave across a lake. Singing silenced. The hush changed into a roar.

Cheering.

The carriage and procession were coming. People pressed forward. No one remained sitting.

Union Jack flags came out of pockets and bags. Smiles widened. Small children pushed between the legs of their parents and strangers. This was it. The train rides, the standing, the waiting. It was about to happen.

As the first horsemen in their golden helmets, white tassels flowing from the tops clipped clopped past, the roar around Heatherbelle became deafening. She didn’t cheer; she just watched, wanting to feed her eyes on every detail: the gold, the glitter, the shining black horses, the beefeaters and coachmen in gold and red tunics, white leggings, black shoes, and hats. Above all, it was the Queen’s carriage that stunned her imagination. For all the pictures they’d been shown, nothing came close to its sheer grandness, to its feeling of otherworldliness. The fairy tale carriage, its curlicues and feathered flutings, its lions and angels, its enormous wheels, all in sparkling gold didn’t belong on damp tarmac with grit crunching beneath its wheels. It should have floated over carpeted avenues bestrewn in red rose petals with birds whistling from the trees.

The Queen in an ermine, gold, crimson, and gem filled crown waved at her and smiled. Heatherbelle waved and smiled back. Head held high. Yes. She’d been a queen too, only a short while ago. She knew how the Queen felt, endlessly smiling and waving until her jaw stiffened and the smile lost its smileyness.

Other closed carriages and open carriages followed with Princes and Princesses, Dukes, Earls, Lords, and Ladies heaped in ermine, crimson, satin, and gems. The finery was followed by uncountable numbers of tunic-covered soldiers and guards, of bagpipes, drums, and multitudes of horses all strikingly shiny. Every so often something ordinary penetrated Heatherbelle’s overloaded gaze: steam rising from a fresh heap of horse droppings, an old man’s tears, crumbs dropped from his pocket when he pulled out a handkerchief, sparrows hopping about to peck at the crumbs, breeze ruffling the guards’ bearskin hats.

Thus, it was over. One short burst of white fur, satin, diamonds, gold and snorting, clip-clopping beautiful horses, and a procession of people, carriages, and musical instruments all sparkling clean in a city impossible to clean perfectly.

Burden of Goodness – Mildred - 1914

The day the disaster happened to his sister, Arthur didn’t for one minute guess what Mildred was about to do. What his father’s temper and mother’s stubbornness had driven her to do. She simply opened the door and walked down their Grassendale well-trodden carpeted stairs that led to the dispensary.

Sometime later the ruckus started.

First the bell rang. The small brass bell was like bells that hung over shop doors to alert shopkeepers of customers. This bell, near the top stairwell connected to a braided cord at the bottom, summoned Father when prescriptions needed to be checked or customers wished to talk to the chemist. Instead of a single pull, the bell jangled repeatedly and the apprentice, Horace Pike, shouted, nay bellowed.

“Mister Lindgren, sir, please sir, come, sir. Mister Lindgren. This is urgent.”

Arthur leapt to his feet. Something had happened to his sister. Fearing the worst, he watched as Father yanked open the door.

“What is it, Pike?” Father shouted.

“You must come, sir. It’s Miss Lindgren, sir. She’s gone mad.”

Arthur panicked. What on earth could’ve happened? What did Pike mean? Arthur darted over to the door.

Mother strode over to the door, pushed Arthur away and stood beside Father.

Arthur slipped around his parents.

All three stared into the dark tunnel of the back stairs as though looking at their own death-tunnel, hellish shrieks drawing them downward.

Arthur knew his beloved sister was in trouble and needed him. Had he dared, he would’ve pushed aside his mother taking the steps quickly, but fire was in the air.

In a way, he didn’t want to know what was going on. Something fierce and deadly, he guessed, and a horrid dread told him that Mildred was on the receiving end.

Over the years, Arthur realized that he’d wanted to remember Mildred with passion in her blue eyes, the way she’d looked before she headed downstairs. With the kind of courage that men had in the Great War when they dragged themselves from their trenches. Bowed down with the burden of their coming death, they ran towards German guns. The guns in Mildred’s case were, of course, what any chemist’s offspring would use to hurt themselves.

Instead of that blue-eyed courage-moment, Arthur would forever remember Mildred in the ghastly way that his young mind witnessed when he pushed open the dispensary door.

In front of the shattered glass lock-up cabinet, where the dangerous drugs were stored, giant pestle in one hand that she flayed at the two assistants whenever they approached—though Miss Carpenter was shrieking more than trying to stop her—Mildred stood, glazed look in her eyes, hair tidy, her mouth chewing and swallowing one handful of pills after another.

Like looking through a paper cut-out of snowflakes—under father’s raised arm, around mother’s wide waist, Miss Green’s arms, through the fuzz of wailing Miss Carpenter’s loosed hair, Arthur watched his parents forcefully stop Mildred’ deadly dining. She collapsed soon after their arrival, no doubt brimmed full of powerful potions.

“Emetic, quick Pike,” Father yelled, business like. “Salt solution.”

His face stark, Pike’s eyes seemed about to pop out like pills. “I don’t . . . uh . . . I can’t remember the concentration, Mr. Lindgren. Can you do it, please? I don’t . . . I might kill her.”

“Kill her, boy? Kill her?” Father’s voice mushroomed out of his beard. “She’s swallowed enough pills and tinctures to kill a horse. If we don’t get it back up, she’s dead.”

Pike’s lip quivered. “Yes, Mr. Lindgren. A horse, sir, yes, sir, but . . . ” His voice trailed off. Then, as if Mildred’s pestle had struck him on the head and awoken his courage, “Concentration, please,” he said, with such burst that Arthur saw a bubble of spit leave his mouth and land on Mother’s bottom poised above her slumped daughter.

Arthur involuntarily snickered, then felt guilty.

“Two teaspoons in four ounces,” Father shouted. “Hurry, boy.”

Pike flew off and returned minutes later with a beaker of liquid, which he mixed with a glass stir stick as he rushed over.

The dispensary, lit by several recently installed electric lights covered by opaque shades, overflowed with glass bottles. Each embellished mahogany shelf, each area of wall dedicated to a pharmaceutical type—tinctures, syrups, non-ingestible liquids in red-ribbed glass, powders, oils, solutions, herbs, dyes—all had their place and their glass-stoppered bottle-style and colour. The bottles’ labels, scribed in a square of gold in abbreviated curly-lettered Latin, were glass themselves. The writing lay beneath the glass label and was thus permanent. Jars, once filled with their rightful contents, would forever be the bearer of that essence, or oil till the end of time. Quite unlike people who could slip between quiet and fury in moments, or worse, who changed from sister to “someone’s girl,” and from there to a person destined to taste death.

No, people could not be labelled like a jar of bicarbonate of soda or tincture of opium that would’ve stayed that way forever if it hadn’t been smashed on the ceramic tiles where Mildred had thrown it after swallowing its contents.

Arthur stared, panicked as his father force-fed the solution into Mildred’s mouth. Much of it spilled to the tiles. With Pike’s help she was turned over. He couldn’t see but guessed Father was finger-sticking his sister. Father had done it to him a few years back when he swallowed a mouthful of flypaper solution by mistake instead of Marmite drink. His mother was supposed to have moved the flypaper liquid but had left it in the kitchen beside the jar of Marmite that she’d intended to use for his drink.

Of course, Arthur wanted his sister to come back to life, to be saved. Yet, buried in the recess of his mind, a little thought dared to poke up its head. His sister might not want to be saved. She might not want to live her life without Charles. Did he have a right to want her to be saved for him? Spending time alone with his thoughts brought a maturity to Arthur uncommon in young lads.

Years from then, when he remembered the moment, he wished he’d let Mildred go, emotionally, because he swore his intense desire had kept her in this realm, albeit to no good purpose.

“Miss Carpenter, go next door. Ask Mr. Howard to fetch the doctor.” Mother liked to order people around.

The shop assistants had finally quietened.

The quiet was unnerving.

Like breaks between claps of thunder.

Like counting the miles from lightening.

From the next unexpected, yet expected, heaven-shaking thunder-rumble.

The shop doorbell suddenly rang.

Except Mildred, everyone startled.

Arthur jerked out of the stupor he’d been in.

Miss Carpenter squealed shrilly, then looked back at the vomit-making activity.

Pike jumped and nearly dropped Mildred’s heavy head.

Father startled so much that his finger thrust deeper. To Arthur’s relief, Mildred body heaved and gave back a large quantity of pill-laden vomit. Once started, there seemed no stopping. Heave after heave covered the tile with its slippery, odorous sludge.

Arthur looked away, disgusted, yet so saddened to see his sister in such an awful state. Whatever happened after this, nothing would be the same. He wanted to cry for Mildred, for himself, except boys didn’t cry.

Miss Carpenter disappeared to call the doctor. Miss Green’s shoes crunched on the broken glass as she went to serve the customer.

“Mr. Lindgren’s daughter’s sick, sir. Apologies for the smell,” she said as if talking about a child who’d eaten too many humbugs. As if, beneath the bottle-filled wall and below the counters and mahogany drawers, a suicide-rescue was not in progress, and Mother, Father, and Pike were not sprawled on the floor in puddles of yellow slime, polka-dotted with chewed pill-pieces. As if the dangerous medicine cabinet were not smashed to pieces, and a blue-ribbed, glass labelled, glass stoppered bottle of tincture of opium didn’t lie among shards of glass and un-swallowed dangerous-medicine cabinet remnants.

Arthur’s sister went to live at the asylum for insane people. She recovered from her suicide, as far as her body was concerned, but her mind never returned to its happy young self.

“Why can’t Mildred come home?” Arthur asked Father. “Why can’t I see her?”

“Her mind is . . .” Father hesitated. “Diminished.”

“What does that mean? Why did you let her become diminished? Don’t you care? Will I never see her again?”

“The asylum is no place for you.”

“I’m never going to take tablets or pills, even if I’m dying.”

Even if I’m a stupid chemist like you, thought Arthur.

“Foolish boy,” Father said.